“It was on the tip of everyone’s tongue. Tyler and I just gave it a name.” —Narrator, Fight Club

First things first, you should probably get your hands on Apocalypse World.

D. Vincent Baker has created something remarkable with Apocalypse World—it’s a major conversation piece and probably a landmark in the development of RPGs. The influence of this game can already be felt throughout various design circles and it’s a conversation you maybe want to be a part of.

Vincent Baker is today’s entry at “Hell Yeah, Gamemasters.” You know about that site, right?

Actual GMing methods and styles are, so often, on the tip of everyone’s tongue. Vincent Baker set out to give them names. I applaud his motive and his decision to pursue the goal. I’m not sure I care for the names he’s chosen. He’s presented his GM principles dressed up for a desert-wasteland post-apocalyptic world, but big deal, right?

Apocalypse World was my first purchase at Gen Con 2010. I set out to get it early on the first day. I knew I needed to be conversant in this game.

I came to the text of Apocalypse World ready to be dazzled, having heard about a handful of cunning hacks for the game online, which implied that this was the hot new technology in indie RPGs. I came to the text wary of its Mad Max-style names and desert-wasteland vision of the post-apocalypse (a vision I’ve spent months trying to get away from as I develop my own post-apocalyptic game, Razed). I came to the text enthusiastic to play the game.

This post started as a report on how the text of Apocalypse World and I don’t get along—as an examination of that moment between reading and play, when an RPG exists only as the possibilities promised by the text. I ended up saying a lot of what I wanted to about that in this Story Games thread (for better or worse). I don’t come across all that well in that thread, but it shows me wrestling with the text pretty honestly. If you want to see my actual review of the Apocalypse World text (as opposed to the game), you can ask for it in the comments. Maybe I’ll post it.

I came away from the text… less enthusiastic. I came away feeling hemmed in and pushed away.

I looked at the game’s GM advice, which is all proven, excellent advice for running one kind of campaign, and I could’ve been championing it. I could’ve been waving a flag in the stands, shouting, “Hell yes, that’s how you do it!” But I felt like it taken something from me instead of having shared something that we had in common.

This is the introduction to the chapter on GMing the game:

There are a million ways to GM games; Apocalypse World calls for one way in particular. This chapter is it. Follow these as rules. The whole rest of the game is built upon this. (Apocalypse World, p. 108)

That is, there can be a genuine question as to whether or not an otherwise successful GM is doing it wrong according to the rules if he approaches the game in any of the other ways out of the million.

Is conflating the craftsmanship of one’s GM style with game rules a good idea? I’m genuinely torn. If making GM guidelines into rules is empowering other GMs, then great. I think pushing me away is probably worth that.

But while I celebrate the idea of explicit, specific GM advice and tool-bestowment in a game text (I tried to do this with the Storytelling Adventure System stories for White Wolf, too), I felt like Apocalypse World was commanding me to withhold good techniques for the sake of running the game in sync with someone else’s personal taste.

Frankly, I’d rather read Vincent’s book describing how to run an engaging fiction-driven RPG session and campaign than have it be given as a few paragraphs of prescriptive game rules in the middle of a book that is so attitude driven that it drove right past my particular interests. (To be clear, I would buy the hell out of that book.)

I’m a little bit old-school. I think it’s fine for an RPG to be broad enough to allow for many different GM styles, which combine with the inherent styles of the game’s art and text to create a variety of campaigns.

One of my favorite parts of exploring a new game or a new game setting is sketching out what a campaign might cover and what it’s voice and style might be like. How can I make Tolkienesque D&D feel like Brian Wood’s Northlanders, for example, or how can I get my Vampire chronicle to play out like The Shield? What part of the game’s fertile turf do I want to explore and where do I want to setup base camp?

The game’s vision and the campaign’s vision are different things that combine, almost alchemically, to create the actual-play experience for a particular group.

Apocalypse World, in contrast, demands a single voice and style for itself—it’s primed to create one kind of campaign. And, to be fair, it seems like a fine, powerful engine for making that kind of campaign go.Even Apocalypse World’s chapter, “Advanced Fuckery,” detailing alternate actions for the game and for other hacks built on the game, addresses the core mechanics and not these GMing rules. The implication being that alternate dice mechanics are fun hacks of the system, and that perhaps the GMing style is the game’s real identity, since it is not up on the lift for modding in that chapter.

This chapter, though, which alludes to things like John Harper’s and Daniel Solis’s Dead Weight and to a Celtic intrigue game, implies plenty of ways that the mechanics of Apocalypse World can be altered to create things that are “Apocalypse World no longer,” but which don’t call for or encourage alternate rules for GM style or principles. But if you can change the mechanics and the tone and focus of the game and still have something that runs smooth… just how essential are these rules of GM style that “the whole rest of the game is built” on? Or, more to the point, how essential is it that they be rules?

If the “Advanced Fuckery” chapter is meant to imply that everything is open to modding and hacking, even the GMing rules, what does it mean that the “whole rest of the game” was built on that single GM style?

Apocalypse World, it seems to me, aims to educate GMs by restricting (potentially overwhelming) options and prescribing a style of play. It does this, I think, with the understanding that experienced GMs will deviate from the rules when they are ready—when they are confident and capable GMs. Take the stone from my hand, grasshopper, that sort of thing.

And that’s fine. But I read Apocalypse World‘s GM advice in the wake of hearing this quote from Vincent Baker. As a guest on this episode of the Theory from the Closet podcast, Vincent Baker said:

“There’s no such thing as a good GM. There’s GMs in alignment with their game and there’s GMs out of alignment with their game.”

I’m leaving out a whole big chunk of material in here about the order of operations that leads from the fiction to the game mechanism and then back to the fiction, because that’s probably a whole other post. Check out Vincent Baker’s post on “IIEE,” though, to get cooking on that now.

I don’t think I agree. Alignment with the game is a fruitful, useful metric, but is it the one true measure of the GM? The implication is that if I attempt to GM Apocalypse World in a manner separate from that put forth in Apocalypse World, I am either doing it wrong or I am no longer playing Apocalypse World.

Who decides the alignment for a game? In the case of something tightly focused, like Apocalypse World, where the projected campaign and the edges of the game’s turf are the same, it seems that the game designer gets all the credit for devising the alignment of the game, and the GM’s task is to stay in alignment with the designer’s vision.

Is it my duty as a GM to uphold the designer’s vision for how the game should be played? Or is an RPG something like a musical instrument, playable however it is practically playable—and let the audience decide if it’s music?

I simply prefer a game that allows its alignment to be partly the purview of the GM, too. That is, a campaign may be subtly out of alignment with a strictly aligned game and still be a valid form of play. Right?

But there’s also a personal issue here, for me. I think I’m a pretty good GM. It’s something I take pride in doing well. In light of Baker’s position, though, what am I? I’m not good, I’m merely in sync with a system. The credit for a good game session really belongs with the distant designer, and the GM simply enabled the system to do what it’s meant to and didn’t fuck it up. Is that right?

Some of this ties into tomorrow’s open-question post, so stay tuned for that.

I’ve said for years that GMing is a skill—a learnable skill—which means you can get better at it. But if all of Apocalypse World‘s GM advice isn’t there to pass on knowledge like a teacher, to help GMs hone their skills, then what is it for? Is it to get them in alignment with Vincent Baker’s vision of a good gameplay experience? Is it to cut out the creative input of the GM over the alignment of the campaign so they don’t fuck up the designer’s precision instrument?

If the mechanics of Apocalypse World run just fine in different milieus, why is only one of a million GM styles acceptable for play? Why is style a rule? Why is my say over the alignment of the campaign being suspended? Is it worth it?

That the restriction is largely illusory—that the rule is as mutable as any RPG rule—is no comfort. That the shackles are made of glass just makes them ridiculous. Why are they rules, then? Because they’re the foundation for the rest of the game, which is demonstrably mutable itself?

I’ve used techniques codified in Apocalypse World for years in things like my D&D game, even though they’re not explicitly called out as parts of D&D. Am I just lucky that such techniques are in alignment with D&D or can I enjoy some pride in having some techniques that help make games exciting, provocative, and clear? Are descriptive abilities just in alignment with all games, or are they something that a GM can learn to do well?

In my experience, part of the creative challenge of releasing an RPG is in understanding that an RPG will be used in ways that you, the designer, might not have used it. Some of those uses will be successes, even though they’re out of alignment with your vision. Inspiring people to play your way is one kind of happy outcome, to be sure, but it’s only one.

What do you think? Is alignment with a game the true measure of a GM? Should we use “game” and “campaign” interchangeably when reading Baker’s quote?

In case it doesn’t go without saying, I may come to regret this post. I may be simply wrong in my opinion. That’s fair. Maybe one of you has the medicine that’ll make me feel better; that’d be great. Until I get that dose, though, I continue to be vexed.

“I’ve said for years that GMing is a skill—a learnable skill—which means you can get better at it. But if all of Apocalypse World’s GM advice isn’t there to pass on knowledge like a teacher, to help GMs hone their skills, then what is it for?”

The MC moves of Apocalypse World passed on GMing knowledge and skill better than any GM advice section ever has because it forced me to repeatedly bump my head against the GMing style it was trying to produce. If I wasn’t doing it right, it showed, and I was forced to actually learn this alternate style. Now, at the end of the campaign, I know that I’ve learned lessons that I will carry into other games in ways that a GM advice section has never done for me.

Hi Will,

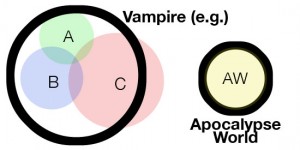

You and I haven’t played games before. Let’s say we were going to sit down to play Vampire. I’m totally coming from perspective C, and you’re totally about A. If we’re good folks we’ll get ourselves into that space that crosses both A and C. We might also tug and fight and have a bad game, because when you say Vampire, I think C and you think A. We both call it Vampire, but we’re speaking a different language.

Now if we sit down to play Apocalypse World, there is just AW. I think this is the advantage. Yes, you as a person lose some flexibility, but if one player loses flexibility so the rest of the players have consistency in expectation, I choo choo choose that.

I don’t think it’s about measuring GM’s, I think it’s about clear game design. Now I think you can do something like the Vampire model you’ve made, if you call out what rules support which letter. If the game doesn’t do that, then it’s a bit of an enigma, which is useful to someone like you who has developed a bunch of skills, and like an artist is creating a game from rules paint, but there are lots of folks who may not have that artistry. I would contend that single circles are better for them. They may be better for everyone, but I’m not sure I know how to defend that position.

The idea that any given RPG should support/allow for multiple GMing styles/techniques is largely born out of the fact that most of the RPGs that have been published have failed to communicate their point of play and failed to provide any useful guidance in how they should be run. GMing then becomes this mysterious body of techniques that gets passed down by oral tradition, which then gets applied by different people to various RPGs with various levels of success.

The funny thing is that this question would seem pretty silly if applied to other types of games. “GM techniques/style” is essentially synonymous with “how to play the game”. I mean, is anyone unclear on how to play Scrabble? Would we have big debates about one person’s “Scrabble technique” is wildly different from another?

AW is the way RPG texts should be. No one is prevented from drifting the game, of course. If anything, they are encouraged; you have to know how something is supposed to work before you can successfully modify it to do something else.

In case it doesn’t go without saying, I may come to regret this post. I may be simply wrong in my opinion.

Honestly?

I think you’re being charitable by assuming there is a dialogue taking place where people other than you are willing to carefully consider things, offer concessions and get to a constructive end. I think you’ll just experience a wordy version of COOL STORY BRO and some Columboing.

That said, I think you’re basically right (I actually used the Venn diagram analogy this past weekend at a convention) and want to see this aspect of the craft developed more. But I think it needs to do so not so much as part of this dialogue as something that develops from your own craft.

Really, the quote makes me think of when I was a kid and got toys like action figures. I never wanted those playsets that basically had a few things to foll around with in a linear fashion (one door, one chute, one secret panel laid out) and a cheap cardboard backing to convince you that something was the Death Star. I wanted toys that were generally inspiring objects — spaceships and robots and toy equipment (I used to buy a lot of spare weapons for my GI-Joes). If necessary, I could do this with a playset, and Mattel couldn’t stop me, but it was a compromise. And you can always tell that people designing toys that work this way are being cheap, and disguising a lack within a narrow way to play. So these rules really suggest some kind of design deficiency — like where you’re not supposed to hold an iPhone 4 left handed. Stuff like that.

“Or is an RPG something like a musical instrument, playable however it is practically playable—and let the audience decide if it’s music?”

Given my recent reading, I’m wondering if the analogy is more like this:

An RPG is like a recorded track. A game designer is the producer. The GM is the DJ.

So, if the DJ is busy cutting up a record, it’s still be music. But is it the music that the producer recorded? Of course not. Does that matter? Depends on the DJ and his audience, I’m thinking. Though, the DJ is responsible for his own creation; the audience can’t really blame the producer if the DJ’s impromptu remix isn’t working for them.

In the same way, if a GM is busy hacking on an RPG that someone else designed, then it’s still an RPG, yeah? It’s no longer the RPG that the designer designed, though, really, if the play group is happy, who cares? But, as I’ve said elsewhere, the “warranty” is voided; you’re playing a related game to the published game, and therefore you have the responsibility for its outcome. If it doesn’t work, you can’t really blame the designer, because you were playing a different game.

(There is, of course, nuance to this last statement that I’m not exploring.)

Also, I don’t think that you should have any reason to regret this post. You’re expressing an opinion in reasonable terms and inviting further comment. So you take a minority view. So what? I’m on record as having hated the text of Dogs in the Vineyard and pretty much all of Vincent’s games until AW. That’s a minority opinion, to be sure. 😉 But, unless there is honest, rational dialogue, there cannot be any advancement of the state of the art.

As an example, I found Malcom Sheppard’s toy analogy (i.e. “inspiring objects”) to be fascinating. I don’t know if I agree that this applies to games or not…but it’s making me think. This is a good thing.

It’s like Things We Think About Games. No one agrees with everything in that book, but it’s useful to be confronted with the Things to begin to form your own thoughts about games.

So, don’t sweat it. I’m glad that you posted.

“There’s no such thing as a good game. There’s games in alignment with the players and there’s games out of alignment with the players.”

I think that’s no less valid than Vincent’s version.

Oh, hey, one more post, then I’ll shut up. For reals!

My sister just started MCing AW for my wife and I. Here is her review of the game text, which provides a different perspective on the text. I offer this as another datapoint for further dialogue about this game.

There are many AW hacks that will call for different GM Agendas and Principles (I know, I’m writing a few). It’s probably an oversight that the Advanced Fuckery chapter doesn’t talk about that.

The explicit instructions of the Agenda, Principles, and Moves are the thing. In your Vampire example, I would MUCH rather have a book that laid out Agenda, Principles and Moves for each different style (A, B, C) instead of leaving it up to me to puzzle out through trial and error over years of play. That’s just my preference as a gamer. I find clear instructions liberating, not constrictive.

Thanks for the post, Will. Hopefully me continuing to engage you on the topic won’t come across as combative or anything.

John beat me to mentioning different Agendas and Principles, but those are certainly things that change in a hack. You’re completely right that Vincent should write more on that, or at least mention it.

As for the alignment thing: I think your musical instrument example is a good one, but that the idea of alignment still exists. If I sit down with my saxophone and try to play something quiet, light and ethereal, I’m not in great alignment with the instrument. Sure, I can play it, and there might be some novelty to my album of saxophone covers of lullabies, but it’s not the greatest fit to the strengths of the instrument.

My take on Vincent’s statement was kind of like that: being in alignment can be a very strict thing, if the game is very focused, or a very broad thing if the game is broader, but you’re still in alignment.

So yeah, an RPG is an instrument, playable however it’s practically playable, but the people who play it well are the ones who understand what the instrument is designed to do and play accordingly. The ones who are ‘in alignment’ with the instrument.

Maybe this is an issue of GMing being “more art than science.” That is, perhaps the hard, prescriptive set of methods for GMing Apocalypse World (which many folks seem to feel are clear, repeatable, easy to learn) conflicts with your sense of your GMing as an art (full of subtlety, instinct and personal style).

Personally, I think there’s room for both in AW (and most games), regardless of what the text might say. Many of the decisions an MC makes are subjective, leaving room for personal interpretation. Clearly you running this game will be different than me running it, or John, Vincent or anyone else, even if we all follow the rules to the letter.

I understand the confusion. AW looks like a traditional game with a GM. Notice though that the role of the player who presides over the game isn’t “game master”, and it’s not just a fanciful renaming. The Master of Ceremonies has a specific role, much like the banker in monopoly or the Lens in microscope. The MC has very restricted powers according to the rules, just like the players do, so that the system works in a particular way.

Of course, it can be drifted just fine, but it’s not GM advice: it’s Rules for the MC that support the design goal of empowered players and a limited MC. You could hack AW to have a GM instead of an MC, but it will be a very different game experience for the players.

I think that Vincent, through AW, is simply saying this: play by these rules and principles and I guarantee you’ll have fun; deviate and you still may, but my warranty doesn’t cover that.

I think that’s all there is to it.

Thanks for all of these thoughtful responses, everybody. I think a lot of you are right about a lot of things.

Someone smart told me earlier today to be more courageous in my position. Instead, I’ve deleted a lengthy comment. I don’t need to dig a bigger hole for myself.

I’ll clarify just one thing, though: John, are you aware of the Requiem Chronicler’s Guide, which I commissioned as soon as I could at White Wolf? I don’t think you could suggest that I’m *for* ambiguous trial-and-error campaign design and communication if you’d read that book.

Will,

John didn’t say you were for anything. He only said what he liked.

I was just talking about my past experience as a GM, Will. Wasn’t putting anything on you.

Judd, I’m just saying that the book John is alluding to—making explicit campaign frames for Vampire, specifically—has existed since 2006.

[I cut the rest of this, as I hadn’t seen John’s post when I wrote it.]

Uh. Ok. I only mentioned Vampire because your Venn diagram was about that. I wasn’t citing it on purpose to ‘get’ you or anything, dude.

If that how-to book exists… good! Books that tell you how to GM are good, right? That’s, like, the point of my response. I want books to give me instructions. AW does, and I like that. If there are Vampire books that do it, that’s awesome!

Why is AW giving instructions weird and bad, but a Vampire book giving instructions is good and wholesome? I’m confused now.

Vigorous agreement, Will. A lot of the work I’m proudest to have written or developed, like the GMing stuff in Gamma World d20, is precisely about supporting players and GMs in working out what they’d like to do and then figuring out how to make it happen. The milieus I like best all open themselves up to work in a bunch of ways.

I’ve come to think that this is a matter of pretty deep temperament – some people simply aren’t happy with the kind of focus that games like Apocalypse World thrive on, and some people simply aren’t happy with it, and some people vary in their happiness based on other factors. I try not to hector people who have priorities other than mine; as a writer and developer, I tried to do what I could to send up signals to the effect of “If you need X present and Y absent, you may not want to get this; it’s aiming to do a lot of Y and not much X.” But I can’t see myself writing about how anyone who likes such a tight focus is clearly doing it wrong.

I think I may have seen the Requiem Chronicler’s Guide sitting on a shelf somewhere or something.

For my part of this conversation, stupid and potentially disruptive as it is, I will say this:

I quite like Apocalypse World. But I like it because I know that the designer was dead long before the book came to my hands, much less long before the game hits my table. The book can say whatever it wants to say about “these are the fundamental rules.” It’s all wasted ink.

(If you want to ask me then, what a designer needs to do to design a game that makes me like it, if I am going to ignore what they say to me explicitly, I can answer that. It may be a little bit difficult for me to actually get across, however.)

But! Despite my like of Apocalypse World, I cannot speak to Apocalypse World players.

Not the folks I play with, mind you. They’re fine, as always.

Nope, I can’t talk about Apocalypse World with folks who play Apocalypse World from the book, or by the book. (There are a few exceptions to this, mostly based on previous years of experience. But even there I have trouble sometimes.)

When I try to talk Apocalypse World with fans of the game, be it on RPG.net, StoryGames, the AW forums, or pretty much anywhere… I feel like I’m being spoken to from a world that sits about 17.67 degrees off the Vertical from the world I live in.

It started with someone saying to me, randomly, that it was cool that Apocalypse World limited the names you could have for your PCs because it meant that some PC names would be the same across different games, so you could compare your Orchid with my Orchid.

I blinked, tilted my head like a dog listening to an old record. I got the second part, I remember the old days of D&D when we could all compare notes about what happened in the Keep on the Borderlands. But the name thing…

See, it just never occurred to me that the name list on the sheets was prescriptive. I’d barely even considered it descriptive. More like suggestions that I was unlikely to take.

But there it was. You can only chose names from that list. Ever. And I still, even after having the whole thing explained to me, sit there tilting my head and unable to get it.

This has been a rousing and polite discussion, but like most on the internet, it’s become mired in personal opinions about subject example (and side comments) and losing the point made with that example.

If I may, Will has encountered what might be THE ‘system does matter’ game. He bolsters this point by including some of Vincent’s statements about his position on this. To wit, (in my own words—likely a misreading) there are no bad gamemasters, there only those who do not follow the rules.

Vincent is the self proclaimed heir to the GNS theory and probably thus to it’s parent, the ‘system matters’ manifesto. AW seems, by Will’s description, to prescribe even the gamemaster’s play. This clearly makes the game’s text, the designer’s word, more important than the consumer’s

This is largely why I dropped out of the Forge Diaspora. I write for the consumer first, offering advice, skeletons and techniques for their improvement; I do not prescribe.

Something like Malcolm said above, I only want to create the inspiring toys.

Seth, I just read that review you linked, and it’s marvelous.

Is conflating the craftsmanship of one’s GM style with game rules a good idea?

No.

And then later buzz says:

The idea that any given RPG should support/allow for multiple GMing styles/techniques is largely born out of the fact that most of the RPGs that have been published have failed to communicate their point of play and failed to provide any useful guidance in how they should be run.

Also, no.

Glad I could clear things up for everyone.

And then later buzz says:

…

Also, no.

Very glib, sir. 🙂

My statement is exactly what games like AW are reacting against, ergo, true. Hah!

And I think “conflating the craftsmanship of one’s GM style with game rules” is kind of missing the point. “Style” is a method of play; the whole point of rules are to lay out the methods used to play the game. If the game relies upon one of he players “barfing forth apocalyptica,” then, by gum, the rulebook ought to mention that.

Regardless, I generally prefer focused games like AW. If a game is not focused, and theoretically can be played with multiple “styles,” then I feel like one inevitably falls into asking the question, “Why couldn’t I just do this with GURPS/HERO/etc?” But I suppose that is a larger question.

Will, there is no reason to regret your post. Lots of interesting discussion here.

I’m not even sure that I agree with me anymore. I keep getting pushed off of my original position—which is not that specificity in games is bad—into spots where I am defending for and against generalities. I mean, I like well-fitted clothing but I don’t have to defend straightjackets to do it, do I?

Anyway, I’m now in the midst of a discussion on this topic via email that is revealing both where I am overstating things and also where I am being misconstrued. It’s enlightening.

In the meantime, really, thank you all for weighing in on this. I’m smarter now than I was two days ago.

What does tool bestowment mean?

Great post. I have yet to read Apocalypse World, but it sounds like it is taking a step farther along a path that was already started in Poison’d.

Ultimately, I think this is a question of taste and personal preference. The people that worry me are the ones who say perfect GM alignment is the way games must be designed. There are people who want prescription on how the game should be run that is tightly aligned with the rules and there others who don’t. They are simply different design approaches.

Fortunately for me, I find both ways interesting!

It all depends on where you place the “creative” value in the art of gaming.

Greg Stafford, who first conceptualized rpgs as art, placed the creative ownership at the game design, the game mastery, and the player levels.

What Baker is doing here is attempting to maintain creator control, and asserting that his method is the best way to play.

Stanley Fish would have a lot to say about this. A big part of the artistic dialogue is that the artist, no matter how much they don’t want to, must relinquish control of meaning and value and use into the community at large. This often leads pretentious, and talented, people to become reactionary against those they deem “aren’t interpreting their works correctly.”

Personally, I don’t think you are advocating GM empowerment enough and are conceding too much to “designer intent.”

Christian, have you actually read Apocalypse World? ‘Meaning and value’ are still in the hands of the people playing the game. I’d actually say they’re more explicitly in the hands of the people playing the game, since the rules say you can’t have a planned plot.

On any kind of thematic level, the AW rules say as much as any great set of ‘art’ RPG rules do. The MC rules are all about the practical: react to players, let the player characters be the stars, and so on.

So, yeah, you probably have a point about some hypothetical game and the designer’s control over it. But this is a game that only goes so far as to tell you how to play it.

I tell ya, were this any other type of game, this conversation would seem quite silly, methiks.

“What? The designer says in the rules that the pieces need to move clockwise around the board? How dare he try to control me like that!”

🙂

Buzz,

Probably true.

Of course, if we were talking about any other medium of creative expression the conversation would also seem quite silly.

“It says here the way to make a great work of art is to follow these rules exactly, and you’ll always end up with a Mona Lisa!”

True, but the part that tends to get overlooked by modern postmodernists is that the greats tend to have a firm grasp on the rules and why they exist before they go about breaking them. Sure, there are prodigies that are exceptions to this, but part of what makes them prodigies is an instinctive grasp of the stuff that gets taught as rules.

Sorry, Brand, nothing personal, but this is a line of argument that has gotten my dander up in the past and I needed to get this off my chest.

@Steve Moss: bestowment

Ug! Please ignore the phrase “modern postmodernists” in my last comment.

*hides head in shame*

I tell ya, were this any other type of game, this conversation would seem quite silly, methiks.

“What? The designer says in the rules that the pieces need to move clockwise around the board? How dare he try to control me like that!”

I love this bit of rhetoric where you get to talk about artistic vision on one hand, but when that vision gets questioned it’s all about complaining that if this were Monopoly everybody would just shut up, so they just should shut up.

Buzz, this isn’t about Monopoly. This isn’t about other games. This is about RPGs. It isn’t even about “story games” since AW is firmly in the tradition of tabletop RPGs. You do not get to argue everyone into parameters where people will just shut up and silently assent. I mean, I know that flies not only in your game community, but in the games themselves. I know you are accustomed to engaging creatively to the extent that you will obey. and that you are looking most strenuously to give your obedience. But outside the bubble it’s just really goddamn creepy.

True, but the part that tends to get overlooked by modern postmodernists is that the greats tend to have a firm grasp on the rules and why they exist before they go about breaking them.

No. Postmodernism already demands an informed process. You can’t toss things into (say) a Foucault-style narrative of significance without research. It’s not “ignored” at all.

Nevertheless, that interpretation of Fish is kind of suspect as he does not argue for a kind of shallow mob-dominion, but for consideration based on multiple ways of knowing — many processes. Frankly, we know better than to take readers at their word, too. In RPGs especially you often encounter this kind of bullshit “dead of the author” argument where someone just whines that their opinions matter the most as readers, and then use the text as a pretext to spout various extremely stupid opinions. Every time you read about WW games being “anti-technology,” or the alarmist crap about Poison’d this is the kind of bullish stupidity at work. It’s not what Stanley Fish is about.

But forbidding an informed (*informed*, not any) approach to a work by arguing that only one or a few praxes are valid is a kind of petty, low-stakes fascism unless, as I said, there’s a moral imperative at work.

My hope and play for the Apocalypse World book is that it teaches people a way to roleplay, including a way to GM. It’s one of the ways that I happen to know how to play, and it’s a fun way, so I want to share it.

If you want to learn how to play that way too, hooray! I wrote the book for you. I hope it works and you have a great time.

If you already know how to play that way, great! You don’t need the Apocalypse World book to teach you. I hope you find other things in the book fun and interesting.

If you don’t want to play that way, okay! You don’t have to. It’s not the only way to play, there are dozens or millions. If you find some other use for the Apocalypse World book, then that’s cool, I’m glad you did.

And if you want to play Apocalypse World without playing it that way, well, huh! I don’t really know what that means, since to me Apocalypse World is its game rules. It has barely any setting, barely anything else that could carry the name. But sure, take what you find useful in the book, whatever means “Apocalypse World” to you that you want to keep, and throw the rest out. My blessings! I hope you have a great time.

(Rrg. In the first sentence, that’s hope and PLAN.)

Sage,

Yes, I have read AW, but my comments were addressing the larger issue of artistic dialogue as a whole. In particular, Vicent’s attempt isn’t to control “creativity” milieu. Instead it is to control style of play. That is still a refusal to release control of the property.

Gerald,

I thought it was funny! Modern Postmodernists should so be a hipster band.

I’m not sure I understand how “style” is being used here. Is it synonymous with “how to run the game”? That would seem strange to me, as to me, “style” means stuff like how Mark likes to use funny accents for his NPCs, Nicole always pre-rolls a bunch of die results before play, or jai likes to use fae as villains. I didn’t think “style” meant how one pushes to conflict or resolves mechanics or whatever. I thought that was what good rule texts were for.

I just don’t really get the objection. The game promises to deliver a particular thing: a game of roleplay. It says that, to achieve what it attempts to deliver, such-and-such rules are to be followed.

Sure, don’t play by the rules, hack it or drift it, but why object? The game is what it is.

Maybe there’s a line I don’t see that others see being crossed. What do people think of the following:

– In Polaris, you must use specific ritual phrases to invoke particular rules. It’s telling you how to play, right down to the exact words you’re allowed to use.

– In Universalis, it says that if you want to hack the rules, you may only do so by introducing (and paying for) a Gimmick within the game session, which may be voted down by the other players.

– D&D 4e tells you to have five PCs to make the math work out, specifies magic item distribution per encounter and character level, and forcefully tells the GM to not mess with the encounter-balance guidelines.

– In A Wicked Age tells you to use the Oracle to come up with the game collaboratively. World-building and plot-construction on the GM’s part is breaking the rules.

– Dogs in the Vineyard tells the GM to make towns with problems for the PCs to solve. The GM isn’t allowed to set up a plot in which the Dogs go off and rob trains while fighting off giant mechanical spiders.

– Every game tells you how to make characters, and are usually exceedingly exacting and uncompromising about how.

I just don’t really get why this one game is being called out for having rules that are provided explicitly to make it do what it promises to do? How is it different from the above?

It isn’t, it shouldn’t be, it can’t be.

Glad I could help.

(Strange, I just got comment notifications on Malcom’s replies today.)

But outside the bubble it’s just really goddamn creepy.

Go, go Gadget Ad Hominem!

Christian, this is probably a topic for another time and another place, but if the game doesn’t control/inform style of play, why do we need more than one game?

From conversations and actual play at PAX, I think it’s less that I don’t agree with Baker’s restrictions on play style (as I think I made clear, I don’t have a philosophical problem with that) and more with the actual language of the book. I don’t much like how it’s written. Again, this is an opinion thing, so wad it up and throw it away as you like.

The stone that sticks in my craw is that I don’t like the idea that, for example, “announce future badness” may become the de facto jargon for provocative suspense or engaging menace in a game. (And don’t get me started on “to do it, do it.”)

Whatever. The point is that AW fans have me much more excited about the game than the book does. This is a problem, in my opinion. Not necessarily one to wrastle about, but there it is.

You’re all welcome to use this space to continue discussion (and I don’t think your point is a digression, Sage, so discuss it if you like!), though, and I’ll keep reading.

buzz, I think style here is “player-driven dynamic sandbox” as opposed to “crime/horror investigation” or “things-go-wrong comedy/drama.” I’d call those styles of games, the things you’re talking about would be techniques, but that’s all just picky semantics.

Go, go Gadget Ad Hominem!

You must of course be sure to show you’re on side with public gestures, particularly those that demonstrate a lack of reflection. Reflection is a pause to think, to explore alternatives, and you believe so very, very strongly that this is a form of failure.

Like I said: creepy.

Like I said: creepy.

Isn’t he great, folks? Let’s give him a big hand!

I think this is a great conversation and I’m glad Will started it.

I participated in the AW playtest and really struggled both with the rules as written (I didn’t understand them) and with MCing the game (I didn’t get how to run it properly). It was such a bad experience that it’s making me rethink my GMing in a way I haven’t done since I was first introduced to indie rpgs about 5 years ago and tried running BW after a career of D&D and GURPS.

In both cases, there was a major trainwreck (in my mind) at the game table and both game experiences were a blow to my confidence and caused me to step back from running games for awhile.

But in the case of BW back then, I ended up moving more towards games I was more (fit?) to run. And in the end, I think it made me a stronger GM.

What will happen this time?

Well, maybe it’s teaching me that I don’t prefer to run certain types of games, even if I enjoy playing them. (I haven’t played AW yet but look forward to it)

And to steer myself towards running/facilitating games I am better suited for my style.

And if AW is causing this many strong reactions from gamers (which I have also read elsewhere), then I think Vincent has done the hobby a service. So bravo to that!