This is about inspiration. This is about narrowing down an infinite array of potential attitudes and ideas into a smaller headspace, a common playground with a common language — someplace where I can say the word viking and conjure the right kind of image. This is about getting our instincts and imaginations to overlap, so we can communicate quicker, visualize sharper, and play together.

This is a primer on some of what makes my current D&D campaign what it is, presented for two purposes: First, because I like to talk about what I’m playing. Second, because I want to talk about how we translate inspiration into a play space.

I’ve given the campaign the underwhelming but somewhat telling title of The Northsea Saga, and I’ve described it on Twitter as “Brian Wood’s Northlanders versus Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.” This post isn’t much concerned with the fantasy lore I’ve cooked up for the campaign — that’ll come later, if you’re interested in it — but about the bloody battleground inspired, to me, by the hard intersection of these two very different sources: one lyrical and one vulgar, one classically poised and one frankly brutal. This is what I’m after, and this is why.

If you’re interested in the Character Builder campaign file used to create characters for this campaign in the D&D Character Builder, it’s right here: The-Northsea-Saga.dndcamp.

In short, it allows game material from a few central books, plus the Skill Powers forthcoming in Player’s Handbook 3.

That lackluster name, The Northsea Saga, is meant to plainly evoke some of what the campaign is based on: the classic Norse sagas, and folklore concerning the people, places, and legends that somehow contact the North Sea and the North Atlantic, even when that folklore is as far removed from real-world history as Tolkien’s Elves. This means I’m drawing on the mythology, geography, and general climate of Scotland, Iceland, Greenland, and Scandinavia, plus a bit of Norse cosmology (put through the filter of fantasy) and some whole cloth invention. This is still a D&D campaign, after all; it has to explain where dragon-people come from and how magic is viewed by the everyday populace. (For example, the Northsea Saga’s equivalent of the Skraelingar will bear only a slight resemblance to any real-world peoples.) These are all in addition to the Tolkien and Wood inspirations, obviously.

(To be honest, if I thought this was something more than a simple home-game, I would’ve given it a richer name. But this is what came out when I needed something to fill an empty field in the D&D Character Builder software, so there it is.)

Why these two sources? What is it I’m hoping to borrow from each and what is it that I’m hoping to end up with? Let’s start at the beginning — what do I hope to capture from each source and deploy in my own adventures:

From Lord of the Rings

You know what Lord of the Rings is — it’s a sprawling legendarium mixing pastoral charm with epic menace. It’s part Norse saga (especially The Silmarillion) and part proto-fantasy travelogue adventure. Here’s what I wanted to take from it:

- A looming, notorious foe. This isn’t something I usually like in my fantasy settings. I don’t usually go in for the Saurons. But Lord of the Rings Online and a recent reread of some things Tolkien (plus a realization that I need to cook up better villains) have me loving the easy dialogue possibilities and dramatic menace that come with big bad guys dwelling in the background. Some of this may come from seeing Voldemort’s effect in the Harry Potter movies, even when he’s hardly around. Whatever. The point is, I’ve played a lot with petty, human foes in the past and I’ve had a taste for big, outright villainous foes for a little while. I’m going to slake that thirst. This has two key effects on gameplay: 1. Players can easily compose dramatic dialogue about their queenly nemesis, Crua the Witch-queen, and 2. it provides the gross pressure of incoming villainy that fuels the nuanced politicking and scheming of the “good-guy” Earls at the other end of the campaign’s narrative.

- A rich and legendary history. Obviously I could get this from actual, Earthly history, too, but what I’m after is the way that Tolkien’s history presses on the present through ancient ruins, storied treasures, and fabled lands. It’s not enough to visit a ruined watchtower, it’s got to have an archaic name, a sad and proud and half-forgotten history, and some symbolic significance to the history or destiny of a main character. In play this means I make up a lot of lore on the fly, thereby expanding and deepening the history of the game world not just between sessions but during play, which is fun for me. This also helps the players feel like their characters are a part of the setting, because I give out a lot of background information without calling for skill checks and other bullshit — the characters live in this world that we the players only visit. They’ve heard legends and lore, they know what’s up.

- Wonder. Tolkien had a gift for balancing ever-present elements of the fantastic with a sense of ongoing wonder. Elves are simultaneously marvelous and earthy, ever-more rare and yet abundant in the narrative. Magic is all over Middle-earth, yet strange and wondrous enough to be fearsome. Wonders abound, yet wondrous they remain. For a D&D campaign this can be tricky, because so much magic is named and quantified. In play, then, I’ve got to work to make spells and arcana mysterious and charming, more like folklore than science. (I think I’m pretty good at this, though.) This extends to fantasy races, which must be remarkable enough to maintain some mystique, and yet common enough that we don’t get tired of every scene starting off with startled characters who can’t believe they’re meeting a Dwarf. I dig Tolkien’s balance there, too.

From Northlanders

You should be reading Northlanders already. It’s a sprawling anthology series of Viking-age crime tales, violent and dirty, with eyes wide open and a deep, rattling roar. It’s part Norse saga and part noir, with complex characters. Here’s some of what I wanted to take from it:

- Short, contained stories. Brian Wood is telling a lot of little stories with Northlanders, some of them as small as one issue. Bless him. This creates the sense of a big world, full of tales. I want that. In an RPG campaign, this can be good because new beginnings can revitalize players. This can also be hard, since a campaign can lose focus if new beginnings mean new PCs emerging as new protagonists every few sessions. If that happens, though, so be it. Northlanders reminds us how to a series can maintain a voice even when it doesn’t maintain a main character. Either way, I want shorter tales because I’m flighty and I may want to jump ahead a whole level of play or an ocean’s breadth.

- A frank, brutal, voice. Northlanders doesn’t use the high-falutin’ language that Tolkien does to create some sort of quasi-ancient demeanor. Instead, Wood translates Viking words into modern, accessible, and aggressively effective dialogue. People talk how people talk, without the heavy slant we sometimes put on period-piece lines. In play, this helps the players get over the hurdle of composing dialogue for their own characters, because they don’t need fake accents or archaic vocabulary. I may do it for NPCs, now and again, but players are in the clear to talk (and inflect!) like people rather than costumed people. That voice goes well beyond dialogue, of course, to character actions and narration. When Vikings are recast as human beings, they become easier to understand and play, even if they’re Elves and Halflings. Northlanders‘ narrators sound like they know what they’re talking about, they sound experienced and worn — I want to combine that with Tolkienesque wonder and arrive at something where characters gasp when they see a wizard, and then cuss as they draw their swords and wade into bloody folklore.

- Inspired by history, populated by humans. Related to the above, but somewhat separate, is the mix of historical and human drama in Northlanders. Not every damn character is motivated to monologue about freedom and stand up to a tyrannical army, even though the stories are set In History. Northlanders is about smaller tales that reveal some insight into underlying issues, larger conflicts, and bigger histories, but without losing the personal tale. Northlanders isn’t about the occupation of Ireland by the Vikings, and it isn’t about the role of women in Viking society, but individual stories draw from those historical issues to create personal conflicts. Since D&D is about roving bands of adventurers, these personal tales that dramatize inherent conflicts in the setting are a good fit for gameplay, too. I’ll be making up a fair bit of lore every time we play — transmuting my inspiration into canon on the fly, more like — and this is useful for that, too. I can take the stories of the players’ characters and extrapolate from them and their foes what the larger world is like. I can write in parts of the larger backdrop during play, so relevance is guaranteed. Or I can ignore the larger context and focus on the PCs versus this one Earl or this one dragon or whatever. Let things get personal. Since the audience, the actors, and the co-writers are all the same people — the players — that personal relevance is vital.

At The Intersection

What good is it to draw out these inspirations and highlight the ways they clash? It defines the boundaries of our dramatic palette. On this end, we have Tolkien’s refined and classical fantasy. On that end, we have Wood’s heightened realism and human plight. In between, we the players have two touchstones within ready reach, with which we can render a variety of characters, situations, and scenes. We can use these touchstones as immediate shorthands to convey a lot of atmosphere in a quick moment, or we can use them to set up expectations… and defy them.

It’s not just that these styles are both present, though. It’s that they’re at odds. We slam them together to make sparks.

We confront Galadriel with a dirty, insane Viking with an elk-head cloak and see how the scene plays out. We take the Earl-succession struggles of The Orkneyinga Saga and put it against a backdrop of Sauron’s ticking time-bomb and see if humankind splinters or fuses. We simply smash the palettes together and arrive at new imagery and character concepts to explore.

Art Styles

Both The Lord of the Rings and Northlanders have distinct visual styles that we can draw on during play. In our first session, when a troop of Dwarves was summoned down out of the rocky hills by our beautiful she-elf wizard, name-dropping Alan Lee pretty quickly set the tone for their arrival. The players’ characters, though, are rough and odd, the survivors of a Viking shipwreck — one of them is even based on a panel of art from Northlanders volume one: “Sven the Returned.”

What I mean, then, when I say Alan Lee versus, for example, Northlanders #17 artist Vasilis Lolos, or “The Shield Maidens” artist Danijel Zezelj, isn’t that there will be any kind of victor. Instead, what I want is a conflict in our imaginations, so that instead of just settling into familiar visual tropes, we’re actively engaging our minds’ eyes and wondering, “What would that look like?”

When a character painted by Alan Lee enters into a landscape painted by Alan Lee, it all fits together. But when a character from Northlanders is confronted with a tangled Alan Lee woodland, or tasked with navigating one of Lee’s watercolor highlands, we don’t know what to expect. This isn’t just exciting, it’s freeing. Players can speculate and invent what might happen, rather than feel like their emulating What Tolkien Would Do.

Styles of Violence

Combat is a major facet of D&D, and both of the properties I’m drawing from approach combat differently. Take Tolkien:

“But a small dark figure that none had observed sprang out of the shadows and gave a hoarse shout: Baruk Khazâd! Khazâd ai-mênu! An axe swung and swept back. Two Orcs fell headless. The rest fled.”

— J.R.R. Tolkien, The Two Towers

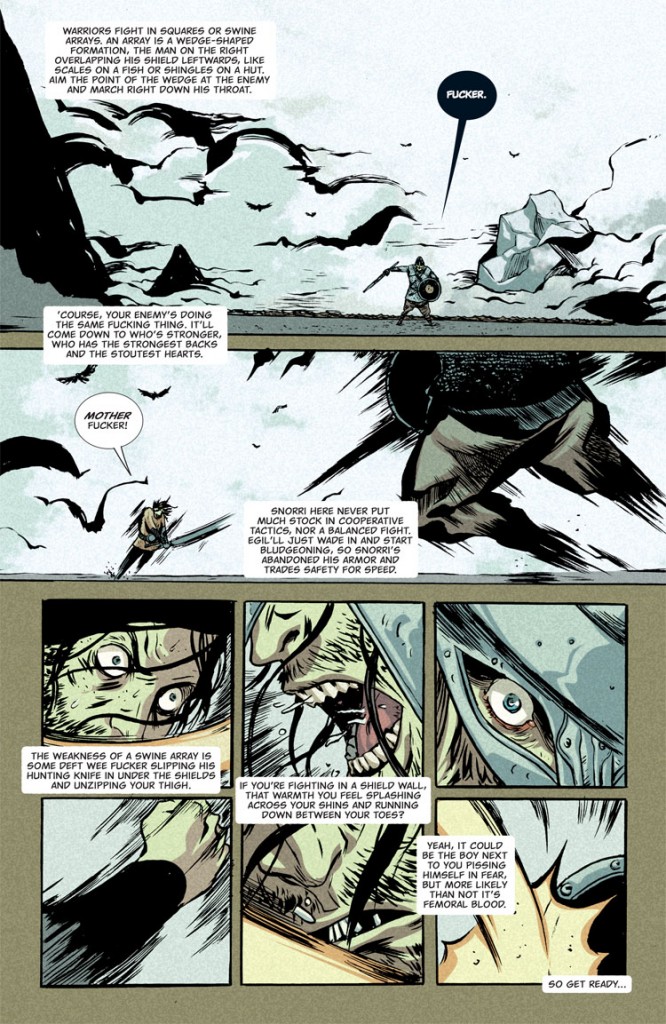

In comparison, we have Brian Wood’s detailed description from a Northlanders script page:

“More spinning counter-moves. Egil makes another rotation, letting the weight of his sword and centrifugal force whip it around. But Snorri has backed up and the sword is six inches short of his throat.”

— Brian Wood, from the script for Northlanders #17

The battlements of Helm’s Deep don’t exactly run slick or sticky with spilled blood in Tolkien’s prose, though presumably there’s plenty of blood when Gimli decapitates his enemies. Tolkien doesn’t mention it, though.

Tolkien often glosses over combat. (E.g., The Two Towers: “[Gimli] soon had work enough.”) In contrast, Brian Wood dedicated a whole issue of Northlanders (#17: “The Viking Art of Single Combat”) to a bout of armed combat between two characters we’d never met before. Here’s a page from issue #17 (click for more, bigger pages) — notice the difference in battle-cries between these blokes and Gimli son of Gloín, above:

This strikes me as being something closer to the nature of a D&D fight than Tolkien’s few sentences. At the very least, it better serves the venue — a DM must be ready with descriptions for violence and its consequences for almost every action the PCs take in battle. A DM needs a lot of details ready in mind to deploy throughout the fight, from the smell of dirt kicked up during a charge to the sound of blood raining on a flimsy shield.

I can single out one of my favorite panels in and issue of Northlanders, and it pertains to this very thing. It’s a panel showing broken links of mail (aka chain mail) in midair, cast off a metal shirt by a sword-swing. This one detail brings the battle alive in a way that Tolkien’s more civil descriptions don’t.

Having this variety of action available is important, not just for the DM but for all the players. Different characters fight in different ways, and not every round of combat is out to achieve the same effect.

The whole character of violence in the Northsea Saga can run the gamut from brave confrontations with almost certain death to tactical, desperate attempts to just survive this fight, depending on the circumstances. One week, the stakes might be right for the players to pit their characters against great evil, no matter the cost, like Tolkien’s men of noble bearing. The next week, the players may just want to survive an unlucky battle and hold onto their characters for one more week. Sometimes the gory lunge, piercing through armor, flesh, and bone, is the right dramatic fit, but sometimes we just want a flash of magical fire and four quietly smoking goblin bodies. By having both sources to draw on for inspiration, we have room to make choices.

Compare Tolkien’s heroes at the Battle of Helm’s Deep…

“‘The end will not be long,’ said the king. ‘But I will not end here, taken like an old badger in a trap. Snowmane and Hasufel and the horses of my guard are in the inner court. When dawn comes, I will bid men sound Helm’s horn, and I will ride forth. Will you ride with me then, son of Arathorn? Maybe we shall cleave a road, or make such an end as will e worth a song — if any be left to sing of us hereafter.'”

— Tolkien, The Two Towers

…with Wood’s sensible soldier-survivors…

Because why lose when you can win? Why die when you can live?

Why not come home when you can come home, farm a couple hectares, develop a really epic potato wine recipe and live to see your grandchildren toddling about?

Why go at a battle, unthinking like an idiot?

— Wood, Northlanders #17

The spirit of Northlanders seems a better fit for the potentially (charitably) picaresque “heroes” of a D&D game. The point, though, is that we need to accommodate both sorts, because individual PCs are different, individual combats are different, and not all fights are worthy of noble sacrifice. D&D characters see a lot of combat, and it can’t all be for the fate of humankind. Northlanders gives us an idea what the everyday battle might be like — and what kind of thinking it might take to live a life of summers spend viking, of summers that make you either wealthy or dead.

Why Say All of This

Hopefully, this kind of explicit examination of inspiration helps us players collaborate as co-creators. Since everything we’re rendering in play is projected only on the inside of our own skulls, but calls for us to share some kind of common vision, this kind of common language is a precious time-saver. We’re not talking about horned-helmet Vikings or noble gilded Thor-like gods, here. We’re talking about people — sometimes desperate, brutal, ugly, proud, dignified, honorable, or savage — who go a-viking to change their lives. We’re talking about people struggling to survive a nasty world made all the nastier by fanged wyrms and a treacherous Witch-queen. We’re talking about brothers fighting over land and titles at the same time that we’re talking about brave adventurers fighting against inhuman hordes for the fate of innocent lives. We’re exploring what happens when we combine bravery with brutality.

What exactly lies at the intersection of Northlanders and Lord of the Rings isn’t clear, and that’s the point. An RPG campaign, like a TV series, is a question, not an answer. Every week we’ll pit these two worlds against each other and see what happens. It won’t always be pretty… but thank heavens for that.

This is intense, exciting, and makes me want to play it.

Do you have any house-rules to reinforce your themes, or is it just a matter of table-convention and roleplay-reinforcement?

Right now, the only house rules I’m tinkering with are special mechanics for Fate and traits for character titles and nicknames — meant to reinforce some Norse tropes, rather than the themes exactly.

Themes, for me, come down more to the storytelling technique at the table. As the DM, I challenge people for descriptions, ask leading questions, and try to provoke difficult choices related to the theme. For example, in this past (first) session, a dead witch asked the characters if they were out adventuring really to seek a cure for their dying king or to secure their own power. “Power for you or your king,” she asked each character… and then she backs it up with a special mechanical effect (which won’t be revealed until the next session). But the way that D&D is built now, that’s hardly a house rule, I think.

If people are interested in this sort of thing, I’ll write more about crafting the setting to support both sources of inspiration, and maybe tackle other campaign-specific topics. I’m just uncertain how much people want to hear about some dude’s game on the Internet.

Speaking just for me, I’m all ears… err, eyes. Quite frankly, and without blowing too much sunshine up yer ass, you’re not “some dude”, and given that Internet discussions of game-craft tend to be buried in either the immensely traditional (dungeon crawls only!) or experimental, it’s nice to hear how the more story-based principles can be applied in a more trad-style environment.

I love the idea of bringing an epic down to the personal level. But with your player characters becoming more human and less archetypal will you have trouble keeping them moving with your story? D&D as I’ve experienced it so far is largely composed of a series of set-piece battles and challenges, and players do so love to wander off in unexpected directions.

Or are you able to build around your characters actions on the fly? Everyone’s had those players that say “Screw Helms Deep! lets wait till they’ve evacuated Edoras and loot the place!”

I do a lot of my DMing on the fly, yes, but I also prepare hooks and scenes that give PCs pretty strong motivations to go and do things. My experience is that my players, who skew older, don’t do a lot of wandering. They don’t want to search for adventure (or misadventure) — they want it to show up as close to the beginning of the session as possible. And that means trusting the DM to deliver without necessarily running off into the woods at the first sign of a slowdown.

This is a benefit of the encounter-driven architecture of D&D, though. Players want a series of fun encounters, and my experience is that they’re willing to buy into the obvious adventure hooks (“Go slay this monster to get an item that might cure the king”) if it means they’ll get fun encounters out of it.

I may be a bit spoiled in this regard, but it’s been a while since I had players go off the reservation too far.

In general, I know the play space well enough that I can keep things on theme, even if the specific action goes haywire somewhere. By devising conflicts, rather than plot points, I can be pretty sure that the story will still come across. The players came to play, and that means they came to play out fights, use their powers, and engage the story.

This kind of talk about inspiration actually helps keep people together, too, because staying on theme or within the atmosphere becomes part of the gameplay.